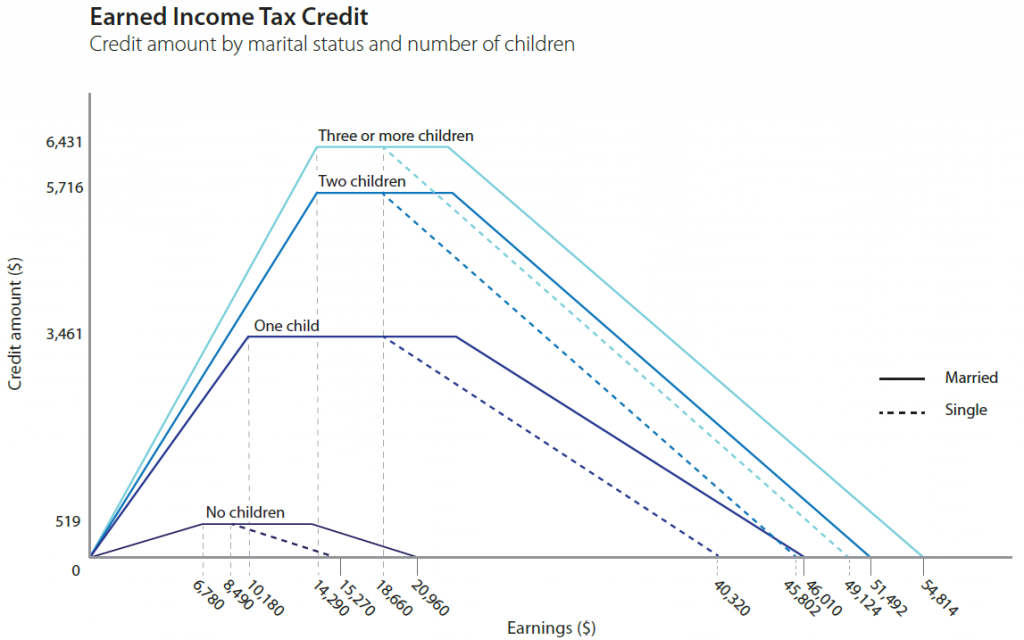

North Carolina is currently considering reinstating a state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). There is a great deal of information and research on the federal EITC. Research has shown that it decreases welfare entries[i], encourages higher levels of education for the children of workers claiming EITC and increases economic mobility[ii], and encourages entry into the labor force[iii], and has a positive impact on infant and child health[iv]. Those are just examples of the positive impacts it has been found to have on low- and moderate-income households. In fact, it is estimated to have lifted 5.6 million people out of poverty in 2018 and 3 million of those were children.[v] If this was not enough reason for bipartisan support, the structure of the EITC also creates policy that many can unite behind. The EITC, at the federal level, is a refundable credit that encourages labor force participation by requiring recipients to be in the work force and increasing in generosity for low-income workers. Depending on the number of children in the household and the marital status of the taxpayer, the credit can be as high as $6,600 (married with 3 or more children). The credit eventually plateaus and then slowly decreases. Below is the structure in 2018. The current federal EITC is structured differently, and it is unclear whether the current structure will be permanent or not.[vi] Thus, the EITC provides important income supports for low- and moderate-income households, with a historic emphasis on those with dependent children, while also encourage labor force participation.

It has been estimated that federal take-up of the EITC is only about 80%, which means that 20% of the workers/households that are eligible for the EITC do not claim it. So, while 889,000 taxpayers in North Carolina claim the federal EITC, bringing $2.2 billion[ix] into the state, there could be considerable unclaimed benefits remaining. Could state policy help close this gap? Possibly. In current research I am doing with my co-author, Thomas Hertz, we are examining two possible mechanisms through which a state EITC could increase federal take-up.

The first is through increasing awareness and information about the EITC. Scholars have identified numerous reasons for incomplete take-up including a lack of understanding and awareness of the EITC. In fact, there has been considerable research and work done to identify ways to increase awareness and subsequent take-up.[x] The impact of mailers, nudges, and other ways to increase participation have typically shown modest effects. One study found that information on the EITC increased take-up, but the impact was short-lived and required subsequent reminders in following years.[xi] Interestingly, another study looked at the impact of state laws requiring employers to notify workers about the EITC and found no impact of the law on take-up.[xii] Thus, while the lack of awareness may be contributing to incomplete take-up, it is complicated and unclear how much a state EITC will increase awareness (through mechanisms like news coverage, advertising it, etc) and how effective that will be at increasing take-up of the federal EITC.

The second way that a state EITC may increase take-up is through increasing the size of the benefit. Standard economic theory suggests that people are rational and optimizers. It is possible that a portion of those who are eligible but do not participate do not because the cost of participation is high enough that it is not worth it. While this may seem far-fetched, especially after I laid out that the benefit could be as large as $6,600, it is less outrageous than it seems. The majority of non-participants do not file taxes because their incomes are low enough that they are not required to. This means two things. First, that those taxpayers would have to bear the cost of filing taxes, which if getting assistance from a tax preparer averages $250 if claiming the EITC.[xiii] It also involves taking the time to do it and investing in learning about the program, amongst other things. Second, it means that the taxpayer’s income is quite low and while technically some taxpayers may be eligible for the maximum benefits and not be required to file taxes, they are the exception.

In fact, we find that the average foregone benefit is much smaller than the maximum, especially for non-filers. That is because we estimate that the majority of these non-filers (60%) do not have eligible children. According to preliminary estimates from our paper, for the single men without children in our data, the estimated average foregone benefit is only $235. For the single women without children the average foregone benefit is only $212. It is slightly higher for married couples without children, at $292. With numbers like these, it is entirely plausible that for some potential beneficiaries, the benefits do not justify the costs. Is it possible that the addition of a generous state EITC benefit might change that cost-benefit calculation?

The answer appears to be, yes. We find evidence that state EITCs do increase federal take-up and the mechanism is the generosity of the benefit. We estimate that if a state were to adopt an EITC of equal value to the federal EITC, federal take-up would increase by more than 3 percentage points (reducing the number of people who are not taking a benefit they are eligible for by about 15%). Of course, increasing take-up is just one possible policy goal of adopting a state EITC. However, increasing federal take-up is an outcome that would not just benefit the low- and moderate-income workers receiving the EITC, but also the state by bringing in additional revenue from the federal program. From a policy perspective, those benefits to the state and its citizens must be weighed against the costs of state EITC, evaluating whether it is something the state wants to pursue and if it does, how it should be structured including its generosity.

DISCLAIMER: All data work for this project involving confidential taxpayer information was done on IRS computers. At no time was confidential taxpayer data outside of the IRS computing environment. Afonso is an IRS employee under an agreement made possible by the Intragovernmental Personnel Act of 1970 (5 U.S.C. 3371-3376). The views and opinions presented in this paper reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the Internal Revenue Service. All results have been reviewed to ensure that no confidential information is disclosed.

Footnotes

[i] Grogger, Jeffrey. “Welfare transitions in the 1990s: The economy, welfare policy, and the EITC.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 23.4 (2004): 671-695.

[ii] Bastian, Jacob, and Katherine Michelmore. “The long-term impact of the earned income tax credit on children’s education and employment outcomes.” Journal of Labor Economics 36.4 (2018): 1127-1163.

[iii] Eissa, Nada, and Hilary W. Hoynes. “Behavioral responses to taxes: Lessons from the EITC and labor supply.” Tax policy and the economy 20 (2006): 73-110.

Nichols, Austin, and Jesse Rothstein. The earned income tax credit (EITC). No. w21211. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015.

[iv] Hoynes, Hilary, Doug Miller, and David Simon. “Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7.1 (2015): 172-211.

Komro, Kelli A., et al. “Effects of state-level earned income tax credit laws on birth outcomes by race and ethnicity.” Health equity 3.1 (2019): 61-67.

[v] Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit” (2019). https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/the-earned-income-tax-credit

[vi] https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-earned-income-tax-credit

[vii] National Conference of State Legislatures. “EITC Enactments 2009-2021.” (2021). https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-earned-income-tax-creadit-enactments.aspx

[viii] Jeannette Wicks-Lim and Peter S. Arno, “Improving population health by reducing poverty: New York’s Earned Income Tax Credit,” Social Science Medicine – Population Health, Vol. 3, December 2017, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352827316300829.

[ix] https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc

[x] Chetty, Raj, and Emmanuel Saez. “Teaching the tax code: Earnings responses to an experiment with EITC recipients.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5.1 (2013): 1-31.

Manoli, Dayanand S., and Nicholas Turner. Nudges and learning: Evidence from informational interventions for low-income taxpayers. No. w20718. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014.

Bhargava, Saurabh, and Dayanand Manoli. “Psychological frictions and the incomplete take-up of social benefits: Evidence from an IRS field experiment.” American Economic Review 105.11 (2015): 3489-3529.

[xi] Guyton, John, et al. “Reminders and recidivism: Using administrative data to characterize nonfilers and conduct EITC outreach.” American Economic Review 107.5 (2017): 471-75.

[xii] Cranor, Taylor, Sarah Kotb, and Jacob Goldin. “Evidence from EITC Notification Laws.” National Tax Journal 72.2 (2019): 1-8.

[xiii] https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NSACCT/725010a8-142f-4092-8b5d-077c2618c728/UploadedImages/IncomeAndFees2019Highlights.pdf