Sitting in the Tax Museum is a stack of losing lottery tickets. It is a good three inches tall. I bought these tickets on eBay. Why can one buy losing lottery tickets on eBay? The answer, as is the answer to every interesting question, is, of course, taxes. If you have made money gambling, you can deduct any gambling expenses up to the amount of income you generated. So, for $10, you could buy $1,000 worth of losing lottery tickets, and so would be able to show fraudulent evidence of $1,000 of expenses to shield $1,000 of your gambling winnings.

This fact, in itself, is interesting, but what does the existence of a market for a very specific tax evasion instrument tell us about the world? I decided to investigate. I looked at time series data on the frequency of these listings and their average price. If I observed prices peaking, or more listings during tax season, it might mean people are getting their return in order, and their fraudulent tax claims defensible under audit, all prior to filing. Which would be interesting. Because there is such a low probability of audit, why not just buy the tickets after you are audited?

This is related to the “traces of evasion” concept in the Public Finance literature. One of my favorite examples of this is looking at cigarette wrappers without tax stamps on them. Here, I am looking at traces of tax evasion to see when people are thinking about doing the evading. Here, the traces have a time stamp. Which is interesting to me. I visited ListingsHistory.com and in about five minutes, I was able to find all the eBay actions for 2014-2017 using the search term “losing lottery tickets.”

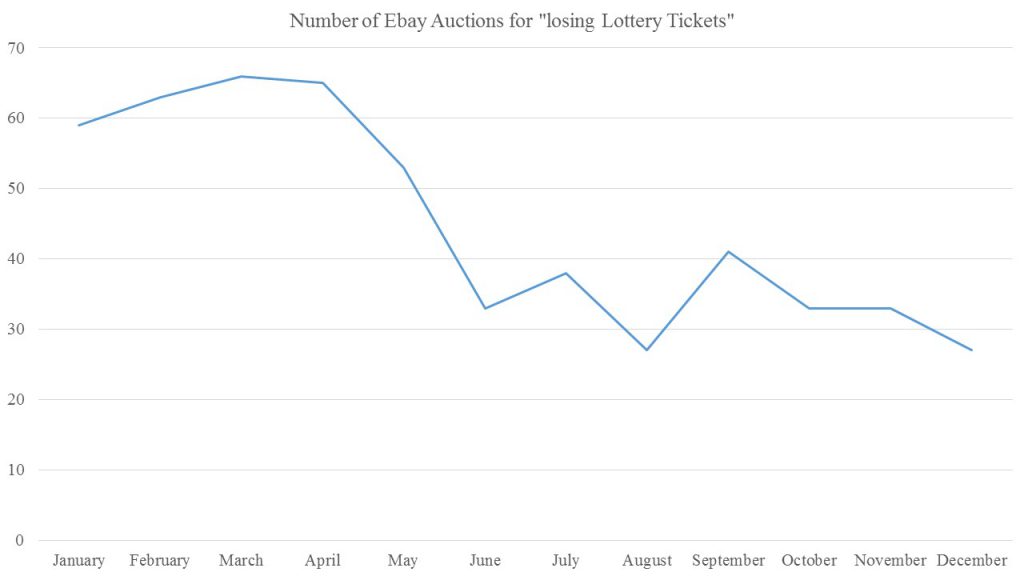

When graphed by calendar month, this suggests a pretty clear trend:

There are online subscription services that allow users to pay for historical eBay listing data, including the price of the item listed (which the graph above does not reflect). The one I used does not allow one to download the data in ways that make it easy to analyze properly, but it does produce graphs. If I squint at the graphs, it appears that February and March were the most expensive time to buy these tickets, when there are more listings (as seen above), and when fewer listings go unsold. But, maybe I am squinting too much, or not enough.

People seem to think about documenting their evasion as they evade, which seems to require a lot of foresight to me.